A dentist-friend recently emailed me a few prescriptions on how I should go about changing myself. Not surprisingly, he holds me singularly responsible for my father's ouster from office. [Papa's government was voted out of power from Chhattisgarh in December 2003: thus began our family's over three-year long 'winter of discontent'.] As things stand, he is not alone in thinking so: Ms. Saba Naqvi, writing for the Outlook magazine, described it rather succintly as 'son-stroke'. I am taking the liberty of publishing these prescriptions followed by the ATR (action taken report) in brackets. I hope that readers of this blog will be gracious enough to offer similar constructive suggestions of their own.

AJ

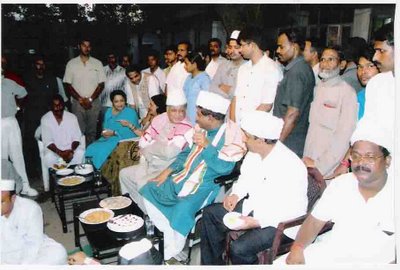

1. Change your photo of a dreamer to a smiling one in your blog site.[What do you think of this one?]

2. Don't write too much on your site, keep it short and simple - so that people can understand and correlate you with themselves. [Visitors will note that posts have gotten shorter, and the language simpler]

3. Don't project yourself to be a cut above the rest - example your favourite movies, music or books you have read/written, to tell you bluntly - no one is frankly interested, all your Orkut friends will try to flatter you, citing your vast knowledge. You should try to project yourself as a normal human being, with whom people can resemble themselves. People of Chhattisgarh don't understand French, they understand Chhattisgarhi. [Interests are listed to form associations with like-minded people; nothing else]

4. Try to win peoples heart rather than trying to brainwash and hijack the brain of 'Boley - Bhaley' people of Chhattisgarh. [How does one win people's hearts? I thought the best way to go about it was by being absolutely honest: telling precisely what I feel. This is what I've done in my blog.]

5. It is not necessary that you serve the people of Chhattisgarh if/when you are in power. When in opposition, your voice is heard more, and seems to be genuine, it's the right time for image building. [Totally agree]

6. It will look as opportunist when you start saying something just 1 year before elections, people's memory is not short, esp. in Chhattisgarh. [Yes]

7. Explain/Describe 1 point at a time, in simple manner to the people, to make it reach their heart. This mistake was done by your father too, I think, so much was tried to explain to people in such a short span, that always it went over their heads. In his first term itself, he opened all his cards. The upper caste people became afraid for their existence in the state. [see point no. 2]

8. No doubt you raise voice for tribals in the state, what about people of other communities, who have worked hard and grown here. If you are a projected leader of Chhattisgarh, you have to represent everyone. Raise voice for upper caste people too, sometimes they are also deprived of justice. [Yes: when specific instances of injustices are brought to my notice against anyone, including people from 'the upper castes', I make it a point to raise it. See for instance, the blog entry on 'A Killing in Dornapal', which describes the killing of a Bengali shopkeeper by a soldier of the armed forces]

9. Move in a two-wheeler, everywhere in Chhattisgarh, (except Bastar) [For a variety of reasons, I am not allowed to drive. Also, I don't own a car. So I have to depend on friends for my transportation needs. Despite warnings to the contrary, I do not have security. The two-wheeler idea does sound good though, if my family- especially Papa after his accident- will permit me]

10. Time is less, Congress is fast loosing ground in Chhattisgarh. It is getting 'Disconnected' and 'Disoriented' from the common man at a fast pace. The Kauravs have again started spreading propoganda at public places against Congress. Who else except you, has to rise, seize the opportunity and show people the way...[If anything has to be done, we have to do it together. I cannot do it alone. I realize my limitations]

to be continued.. Read More (आगे और पढ़ें)......